Hiberno-English, 'Passing' and Pedantry

Why language is a battleground of class and identity

“I’d naw and aye

And decently relapse into the wrong

Grammar which kept us allied and at

Bay.”

- Seamus Heaney, ‘Clearances’, 4, 12-14

I am fascinated by the concept of ‘passing’. In contemporary discourse, the term is most commonly used by trans people to characterise the experience of blending in without incongruity between how a person identifies themselves and how others see them. However, the concept is useful in any scenario where you might feel a strong desire to be treated or seen as someone who belongs, but may feel – or may be encouraged by others to feel – that you don’t. Regardless of the context and whether you do or do not objectively ‘fit in’ in a particular environment (though that idea itself seems quite reductive and subjective), a wish to ‘pass’ is something that can be a great source of stress and very injurious to a person’s confidence. It comes ultimately from a fear of being ‘found out’; of trying very hard to blend into a particular environment or community. I always remember my English cousins, born to Irish parents, telling me they were Irish when they visited most summers during my childhood. They would say this in the flat clip of a London accent, and I did not understand how they could consider themselves to be what I was when it seemed so clear to me that they weren’t.

The fault was mine, of course. I couldn’t have adequately defined what being Irish meant if anyone had asked me. I was rejecting their statements based solely on emotion. They didn’t speak or dress like ‘us’, they didn’t live among ‘us’, so they were not ‘us’. It seemed simple enough, but then, I was about ten. I can remember feeling almost angry with them, as though in claiming to be what I considered myself to be, they were trying to take something from me; as though Irishness is a finite resource, and one to which I had some inherent right to stand as gatekeeper.

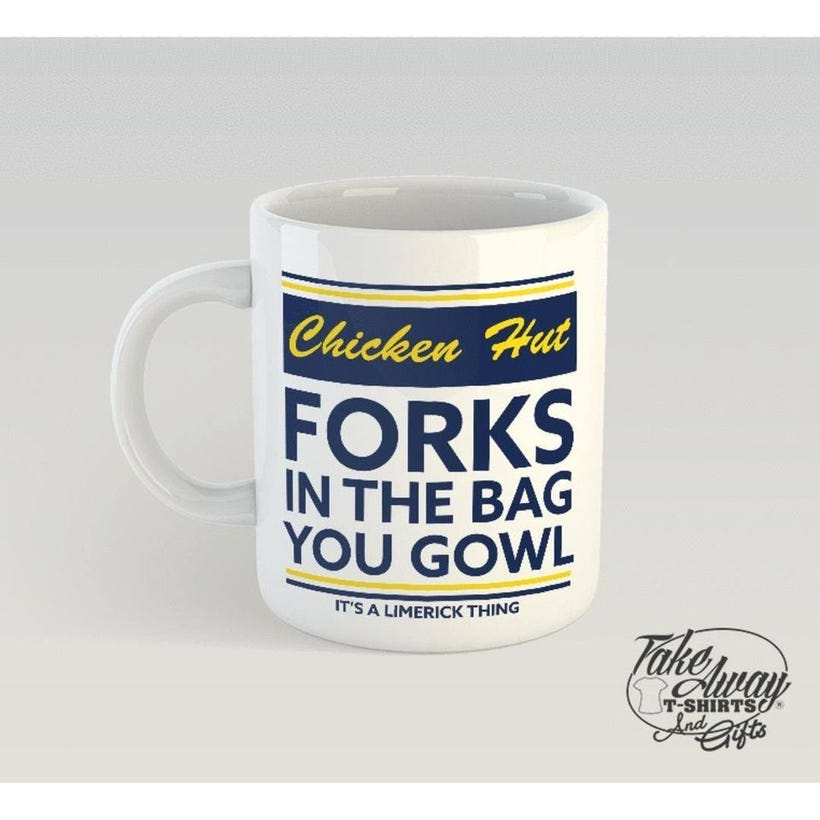

Though I didn’t have the language for it then and the concept was much too challenging for a child to navigate, I was grappling with the knowledge that my cousins did not pass. Their outgroup accents, phrasing and interests all revealed them to be claiming an identity that they could not convincingly perform to members of the ingroup. When they didn’t understand the words and phrases we used, or spoke in their flat, foreign tones, it seemed clear to me that in saying they were Irish, they were really saying they would like to be Irish. With the xenophobia of an ignoramus or a child, I disliked them intensely for refusing to accept what I decided they were, and I thought no more deeply about it.