I Don't Think We're Living in The Handmaid's Tale

Sign up for session 7 of the Peak Notions Book Club. We're reading a feminist dystopian classic

The book club is a paid subscriber perk, and this is going to be an especially good one! I’m offering 20% off paid subscriptions just for today. A paid subscription gets you access to audio content and bonus writing, the Peak Notions archive containing hundreds of written and audio articles, the weekly app chat and the Book Club sign-up sheet (session seven is linked below and there are fifteen spots up for grabs!). Thank you for supporting what I do and making Peak Notions a reality!

“Nolite te bastardes carborundorum. I didn’t know what it meant, or even what language it was in. I thought it might be Latin, but I didn’t know any Latin. Still, it was a message, and it was in writing, forbidden by that very fact, and it hadn’t yet been discovered. Except by me, for whom it was intended. It was intended for whoever came next.”

-Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

The link to the Peak Notions Book Club Sign-Up Sheet is at the bottom of the page

The Irish Embassy here in Australia held a panel on women in media last week in honour of St. Brigid’s Day (Lá Fhéile Bríde), and kindly asked me to be a part of it. The day marks the traditional beginning of spring in Ireland but is also considered an opportunity to acknowledge women’s creativity and contribution to Irish culture. It was a really interesting event (and if you came along it was lovely to meet you).

At one point during the panel, I said the fact that I am a woman is — I think — the least interesting thing about me, and that I would love us to collectively reach a point where that was reflected in the external world. I’m not sure how the comment landed with the mostly female crowd in the room at an event where I was asked to talk about my experience of working in media as a woman, but I meant it.

I balance feeling weary of our culture’s endless obsession with gender against the knowledge that because of this obsession, it’s necessary to continue talking about it. Particularly as gender divides in ideological and political affiliation widen starkly and men and women appear to consider one another less charitably overall. You don’t have to linger long on any social media platform before you’ll happen upon pretty pathetic misogyny from some knuckle-dragging Tate acolyte with the intellectual latitude of a balled fist, and we spent a good five or more years there where “men are trash” was considered a valid and sane political statement by swathes of educated women. The idea that these reductive and dehumanising approaches to thinking about gender do not feed into one another strikes me as myopic.

I’m a woman but I’m a lot of other things too — things I chose, or earned, or happened upon through experience. I don’t weigh this one non-volitional identity label as being more interesting, valuable or relevant in the world than the countless others I, like all of us, might reasonably lay claim to or have foisted upon me. In a cultural environment where so much is understood through a gendered lens even when there are more appropriate lenses through which we might be gazing, it’s often seen as suspicious to say ‘I don’t really care about gender’. It shouldn’t be. Like the rest of us, I just live in and must contend with a world that cares about it far too much. I don’t want to look at any person and presume to know anything about them as an individual based solely on their gender. It makes me feel both depressed and bored that this could be considered controversial or strange.

So I’ve been reluctant to choose this book for the next session of the Peak Notions Book Club for a while, despite its fascinating philosophical roots and implications. Despite the fact that I’ve read it many times and that it has such cultural reach and resonance. My father built a bookcase for our living room when I was a kid and bought two boxes of second hand, thereafter largely untouched, books to fill it. A battered copy of the Handmaid’s tale from the late 1980s was one of them.

I found it on the shelf one day a decade or so after my father built the bookcase, and read the book in one sitting (it was probably my first ever encounter with philosophy of any overt kind), and it had me before I realised what it was that I was reading. Its simple prose. The characters who feel at a distance from you, as though you’re watching them through the distorted curve of a glass dome. The cacophonous noise of the unspoken, shrieking its way into the spaces between the dialogue. The chasm between appearance and reality so vast that the latter becomes amorphous. Not a state of being but a question.

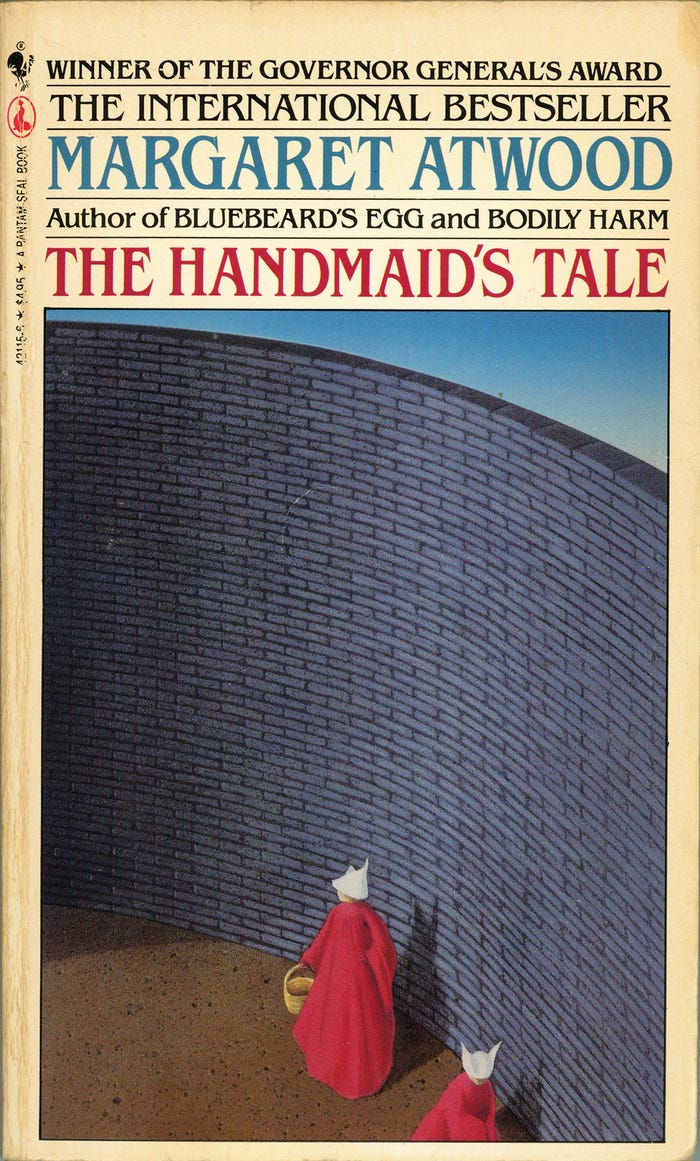

This was the cover art of the well-read copy I found on our book shelf as a teenager. I read it in one sitting and walked around in a daze for a while afterwards…

It is a book that is profoundly unsettling at every level from its mechanics and its voice to its plot and the questions it leaves you with. No matter your ideological inclination, it gives you a good hard shake and out come your lazy or hitherto concealed presumptions about the world and people who live in it. We like to think we know what we’d do if we found ourselves living in Gilead.

The Handmaid’s Tale depicts a futuristic dystopia in which a totalitarian Christian state called the Republic of Gilead has overthrown the United States government. It follows a central character named Offred and considers questions of female autonomy, independence, resistance and individuality. The book was written in 1985 and is not just a work of second wave feminism, though it is that. It’s also a work of science fiction, which is classically a philosophy-rich genre, as it allows us to imagine alternative possible worlds and ways of being. The book enjoyed a major resurgence with the HBO adaptation which first aired in 2017.

The Handmaid’s Tale is about far more than gender. It is about power, politics, freedom and the gap between abstract ideas and how they are actualised. It is relevant to all of us and serves as a warning of the potential outcomes of leaning into coercion, moral absolutism and the idea that ‘good’ ends justify any means we might take to reach them. As a teenager growing up in an Ireland where there were no abortion rights and sex education was delivered by nuns who carried a ‘metaphorical’ big stick, I walked about in a blur for a couple of days after first finishing the book. I could not shake the feeling that I had read something subversive or forbidden. ‘What have I just consumed?’, I thought. ‘What is this grating weight in my guts? This sense that the world looks different now? What on earth have I done to myself?’ The right book at a formative moment will do that.

During Trump’s first term in office, everyone went a bit nuts. Or perhaps it began before that, but you know what I mean. Social media was aquiver with accusations that we were - literally - living in The Handmaid’s Tale. Its signature scarlet capes and bonnets became striking symbols of the systemic annihilation of women’s autonomy. And look, the thing is, we weren’t. We aren’t now either, despite the strength of feeling in the air. Semantic inflation disempowers extreme language for when we actually need it to accurately describe reality. We’ve had four very bizarre years since the end of Trump’s first term and are doubtless in for four more (just of a different flavour) if he makes the distance.

No matter where you stand, there is a sense that everything is unpredictable. Everything is unsettling. It’s a feeling that extends beyond any one geographical location and leaves us with a pervasive worry that the future is uncertain. We cannot reliably imagine the shape it will take or predict the ideas that will dominate the story we tell ourselves about how the world works and what we should believe. That space between appearance and reality stretches beyond our sight line and we feel as though we are tipping off the edge of what we know.

It seems important to say that this isn’t a book club session focusing on abortion rights. It would be zero fun for any of us if anyone came along buckling under the weight of their own moral rectitude. While it’s certainly relevant to the discussion, I think we’d impoverish our reading of the book and our discussion with one another to focus solely on that (and I say this as a decidedly pro-choice person who has publicly defended that position on numerous occasions but also recognises that there are internally consistent arguments in favour of being pro-life. I just don’t agree with them). Every book club session so far has been a delight — warm, open-minded people gathering with genuine interest in the differing perspectives of other people. I want this session to be the same.

This is why I’ve done something I usually don’t, and made clear where I personally stand on the issue of abortion, which has unfortunately in some ways subsumed the wider context of this rich and complex little book. It’s so that when I write what follows you’ll know I mean it: you are welcome at this book club session regardless of your political orientation or your gender. I don’t want to be a preachy bore but if you believe that your position on an issue is absolutely the only one compatible with being a decent and thinking human being, you won’t enjoy this session of the book club. I’m not sure Peak Notions overall would appeal to you. You’d be constantly irate at every column. This all sounds quite contentious but it isn’t — I write it to ensure that the session is not contentious. As someone who campaigned in the run up to the Irish referendum on abortion, I’ve had my fill of morally superior pro-lifers and morally superior pro-choicers shouting at one another about how it is we, in truth, who are morally superior.

If you’re compassionate toward people who see the world differently to you as well as those you agree with and if you’re interested in this book, then please do come along. No other criterion is relevant here. Except being a paid subscriber, unfortunately. I have to keep the lights on!

So. That’s what will orient our next session of the Peak Notions Book Club and, I hope, your reading of the book if you are attending or just interested in reading along independently. We’ll be stepping out of the crushing imminence of a spasmodic news cycle to consider this book in light of the time in which it was written, the one in which we now live, and the universal lessons it can teach us about epistemic humility, human dignity, morality, justice and the worst capacities of human nature. And yes, gender. But I continue to cross my fingers for that post-feminist utopia where nobody cares a jot about gender, because nobody needs to.

You don’t need any background in philosophy to come along to this session or to find value in the book. If you do have a philosophy background, the discussion should still be interesting for you!

The book club is my way of thanking paid subscribers who keep Peak Notions afloat, and of building community here. It takes research, work, and admin (which is not my forte oh my goodness!) so for that reason it’s open to paid subscribers only. There are 15 spots available for the sixth Peak Notions Book Club session, which takes place on Zoom at 8pm UK/Irish time on Thursday April 3rd. You can get all the details (including the confusing time zone stuff!) and put your name on the list via the sign-up sheet linked below:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Peak Notions with Laura Kennedy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.